April 9, 2007 — Iraqi officials jailed two young men in the summer of 2005 for allegedly pocketing the wages of hundreds — if not thousands — of Iraqis working for the Sandi Group, a Washington, DC, firm doing a multi-million-dollar business in Iraq as the leading subcontractor to DynCorp’s $1.2-billion Iraqi police training contract, according to sources familiar with the two men.

People working with Sandi who should know the details of the young Kurds, known as Nashat and Sabah, say they don’t know or ignore the question.

How much money did they allegedly skim from payroll?

Company executives with The Sandi Group declined comment, but inside sources say salaries for Iraqi security workers averaged around $600 a month, and Sabah and Nashat are thought to have skimmed $200 off each monthly salary. Sandi documents represent Sabah as the chief of finance for the Sandi Iraq operations and Nashat as the chief of staff. If the two were in charge of a thousand workers, that could be $200,000 a month. Multiplied by 12 months and it starts adding up to big money: $2.4 million.

“When a worker complained, he would be threatened with being fired,” one former Sandi employee says, who recalled Nashat driving around Iraq in a car with trunk loads of cash for payroll.

The Sandi Group and its affiliates once boasted of employing 7,500 Iraqi workers and claimed to be the largest employer in Iraq during much of 2004 and 2005.

Former Sandi employees recall Nashat and Sabah as two handsome and charming men from an area around the northern Iraqi town of Zakho, near the Turkish border. Zakho also is the hometown of Rubar Sandi, the hard-driving businessman and head of the company bearing his name.

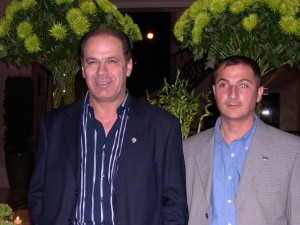

Employees recall Sandi fondly introducing Nashat and Sabah as his relatives — some say Nashat even changed his name to Sandi. But the familial relations were more an expression of close national bonds and affection rather than blood. (Others remember Nashat’s last name as either Younis or Hamed; and Sabah’s as Permos or Bermos. Records represented as belonging to The Sandi Group provided by one former security guard identify them as Nashat Y. Hamed and Sabah Abdul Waheed Bermos.)After immigrating to the United States in the 1970s, Sandi earned advanced degrees in business and economics and staked out a successful career as an entrepreneur, developer and financier. Now in his mid-50s, Sandi also cultivated friendships with prominent Republicans and became an active voice in pushing for the liberation of Iraq at the US State Department where he was an advisor in a pre-war planning effort, the “Future of Iraq Project.”

Sandi returned to Iraq with the 2003 liberation and quickly scooped up interests in major hotels that were leased to other contractors, took an immediate interest in reconstruction, invested in the Al-Ahali Newspaper, and assembled the largest private security force in Iraq — said to have numbered in the thousands.

“The Sandi Group was like an octopus,” one former employee says.

At one time, sources say Sandi even entertained a bid for building the new $592-million US embassy in partnership with Philip Bloom, an American businessman who pled guilty in April 2006 to conspiracy, bribery and money laundering in connection to contracts in Iraq unrelated to Sandi. Although Sandi lost out on the embassy project, the State Department did award the company an open-ended agreement for work in Iraq when needed, including on the new embassy project.

Rubar Sandi boasted of his willingness to hire thousands of Iraqis and said it was fundamental to demonstrating support for the Iraqi people; something he encouraged other companies to do as well. Among those Iraqis that the company hired were Nashat and Saba.

Rubar Sandi boasted of his willingness to hire thousands of Iraqis and said it was fundamental to demonstrating support for the Iraqi people; something he encouraged other companies to do as well. Among those Iraqis that the company hired were Nashat and Saba.

“They knew Baghdad,” said Louis Brown, who ran Sandi’s Iraq operation until autumn 2005 and was then based in Washington, DC as vice president of special projects until last spring before resigning. “I trusted them with my life.”

Nashat, who began work with Sandi as a driver, and Sabah as an interpreter, soon rose to the highest levels of management in Iraq, Brown said.

Asked in March what happened to Nashat and Sabah and where are they now, Brown replied tersely: “I don’t know.”

One source laughed when told of Brown professing ignorance of his two Iraqi lieutenants, Nashat and Sabah. Loyalty and friendship may just be trumping candor.

“That sounds just like Lou,” said the former employee. “But he knows exactly what happened to them and why.”

First of all, thank you for your service, Kadnine! It’s good to get fedacebk from those who’ve served. Those ads are breath-taking, aren’t they? To see Iraqis moving their own people toward the future… it’s such a special moment in the history of this world.All the men and women in the Armed Forces (US and Coalition) have put so much of their own blood, sweat, and tears into this effort, not to mention the sacrifices of the military families who do the same right here on the homefront. For the rest of us who can’t be there to serve, we’re here to thank Freedom’s own warriors and cheer every Iraqi on toward their new future knowing how very important this election is to our War on Terror. Iraqis, your democratic cousins here in the USA and in the coalition countries are crossing our fingers, saying our prayers, and hoping for the best on your first election day!